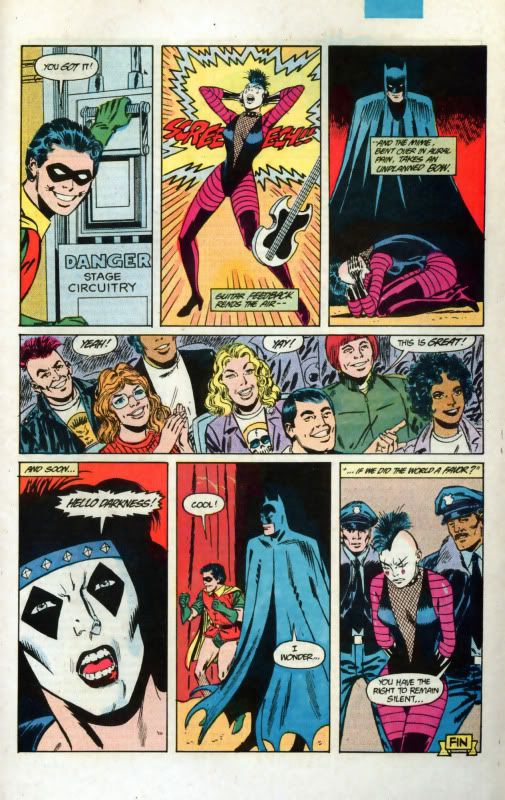

Mime must be one of the most unpopular art forms. It's up there with performance poetry - although that has a New York branch that features plenty of swearing, and hip hop has given it some street cred - and Morris dancing. The ubiquitous white-faced busker, made so popular by Marcel Marceau than brilliant radio comic and low-rent TV comedian Kenny Everett parodied him for a cheap laugh, has become a cypher for unimaginative street theatre. Hulk Hogan smacked one in the face, and Robin out of Batman electrocuted one for applause.

Mime must be one of the most unpopular art forms. It's up there with performance poetry - although that has a New York branch that features plenty of swearing, and hip hop has given it some street cred - and Morris dancing. The ubiquitous white-faced busker, made so popular by Marcel Marceau than brilliant radio comic and low-rent TV comedian Kenny Everett parodied him for a cheap laugh, has become a cypher for unimaginative street theatre. Hulk Hogan smacked one in the face, and Robin out of Batman electrocuted one for applause.It doesn't matter that the Lecoq school has made clowns a little hipper at the past few Edinburgh Festivals, and that the buffoon, a kind of predatory clown, has taken the mime into darker territory. Actually, the name of Lecoq usually gets a few cheap laughs.

Never being one to buck a trend, I am going to begin my investigation into mime not by explaining the etymology of the word (it's from the Greek, meaning to copy) or connect it to the grand philosophical idea of mimesis (Plato's bugbear, the act of copying). Instead, I shall recount a tale I discovered in the Derrida for Beginners book about how a mime died.

It's the story that has everything: a mime being stupid, a connection to the mighty school of deconstruction, sexual jealousy, French literature and an example of how serious the mime can be.

So, there's this mime, right. His name is Pierrot. Being a mime, he can't satisfy his wife - maybe she wanted some dirty talk. Anyway, she goes off and has an affair. Pierrot finds out and, this being a performance, dramatically considers various ways to off her. He settles on tickling her to death.

But he's a mime, see, and this is a pantomime. He acts out his revenge fantasy, playing both himself and the victim. He alternates between tickling and being tickled. He's enjoying himself so much, miming away two parts, that he gets carried away. Then the picture of his wife comes to life and starts laughing at him. He can't stop the tickling - he's enjoying it too much. Unfortunately, it turns out that the cheeky tickle wasn't such a stupid murder weapon. It works.

Pierrot tickles himself to death.

Derrida then explains how the description of this performance by Mallarme - itself based on a booklet describing the original performance - posits a challenge to the Platonic idea of mimesis. I don't have a hope in hell of understanding that.

However, I am interested in this story because it might help me get to the basis of what mime can do, when it isn't standing outside the pound shop pretending to be stuck in a glass cage. What Pierrot is representing is impossible. God knows, I've tried to tickle myself, but I can't. And beyond that, can someone be tickled to death?

I suppose it's possible. It's a bit James Bond baddie complex, but it might happen during a BDSM session that gets out of hand.

Either way, what the mime seems to be up to is... telling a symbolic story through movement. Leaving aside Derrida's meta-readings, Pierrot's idiot drama is a fairly good allegory for the dangers of erotic obsession.

Maybe mime can be understood as a mannered system of story-telling. Stripping away the superficial details (the white face paint, the striped shirt and funny trousers), leaving behind a movement vocabulary that can carry a narrative.

No comments :

Post a Comment